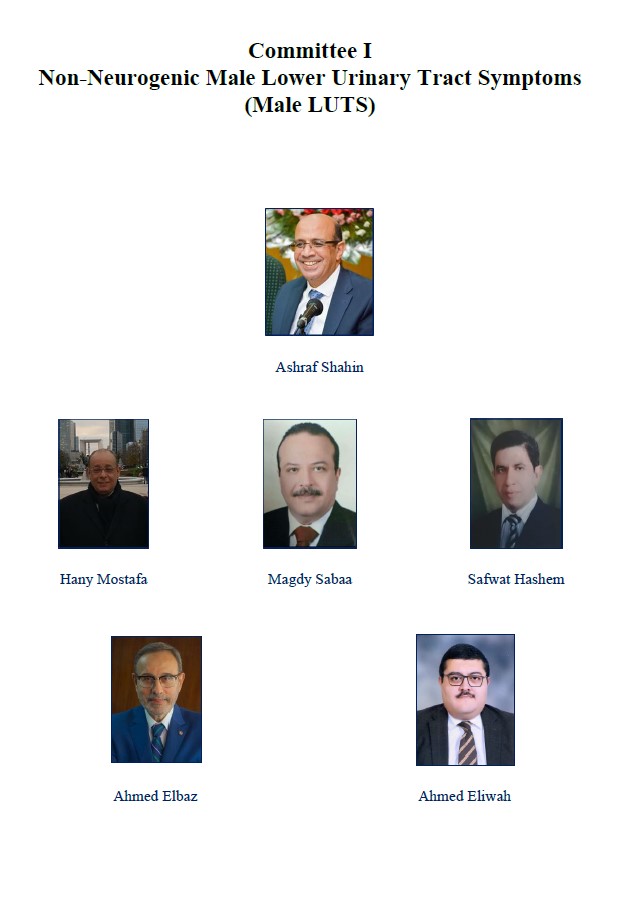

Committee I

Non-Neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (Male LUTS)

Prof. Ashraf Shahin, Professor of Urology, Zakazig University

Prof. Hany Mostafa,Professor of Urology, Ain Shams University

Prof. Magdy Sabaa Professor of Urology, Tanta University

Prof. Safwat Abo Hashem,Professor of Urology, Zagazig University

Prof. Ahmed Elbaz, Professor of Urology, Tudor Bilhars Institute

Dr Ahmed Eliwa, Assistant Professor of Urology, Zakazig University

Contents

- I.1 List of Abbreviations

- I.2 Abstract

- I.3 Introduction

- I.4 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION (Medical History)

- I.5 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION (Assessment of erectile function)

- I.6 Conservative treatment (Watchful waiting, WW)

- I.7 Pharmacological treatment

- I.8 Surgical treatment

- I.9 Minimally invasive procedures.

- I.10 Indwelling catheters.

- I.11 Post-prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence (PPI)

- I.12 Conclusion

- I.13 References

I.1 List of Abbreviations

- 5-ARIs - 5α-Reductase Inhibitor

- AUA - American Urologic Association

- AUR - Acute Urinary Retention

- AUS - Artificial Urinary Sphincter

- B-TURP - Transurethral Bipolar Resection of Prostate

- BEP - Bipolar Enucleation of the Prostate

- BOO - Bladder Outlet Obstruction

- BPH - Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- BPO - Benign Prostatic Obstruction

- BVP - Bipolar Vaporization of Prostate

- CAM - Complementary and Alternative Medicines

- CAU - Canadian Urologic Association

- CKD - Chronic Kidney Disease

- CPU - Conformal Planning Unit

- CT - Computed Tomography

- DHT - Dihydrotestosterone

- DO - Detrusor Over activity

- DRE - Digital Rectal Examination

- EAU - European Urological Association

- eGFR - Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- EjD - Ejaculatory Dysfunction

- EUG - Egyptian Urological Guidelines

- FVC - Frequency Volume Charts

- HoLEP - HoLmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate

- ICS - International continence society

- IFIS - Intra-Operative Floppy Iris Syndrome

- IPP - Intravesical Prostatic Protrusion

- IPSS - The International Prostate Symptom Score

- IPSS-Arb - Arabic version of the IPSS

- KTP - Potassium-Titanyl-Phosphate

- LBO - Lithium Triborate

- LUTS - Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

- M-TURP - Monopolar Transurethral Resection of Prostate

- MRI - Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- NICE - National Institute for Health Care Excellence

- OP - Open Prostatectomy

- PAE - Prostatic Artery Embolization

- PCa - Prediction Of Carcinoma Of The Prostate

- PDE5Is - Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors

- PFS - Pressure flow study

- PMD - Post Micturition Dribble

- PPI - Post-prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence

- PSA - Prostate-Specific Antigen

- PUL - Prostatic Urethral Lift

- PVP - Photoselective Vaporization of Prostate

- PVR - Post-Void Residual Urine

- QoL - Quality of Life

- ThuLEP - Thulium Laser Enucleation of Prostate

- TRUS - Transabdominal or Transrectal US

- TUIP - Transurethral Incision of The Prostate

- TUMT - Transurethral Microwave Therapy

- TUNA - Transurethral Needle Ablation

- TURP - Transurethral Resection of The Prostate

- UDS - Urodynamic studies

- UTI - Urinary Tract Infection

- VGUG - Voiding Cystourethrogram

I.2 Abstract.

I.2.1 Objective

I.2.2 Method

I.2.3 Result

I.2.4 Conclusion

I.3 Introduction

I.3.1 Methodology

- Five guidelines (including their latest updates), namely, European Urological Assoliciation (EAU), American Urologic Association (AUA), National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) and Canadian Urologic Association (CAU) and International continence society (ICS) (1-5).

- Review of several guides, recommendations, position statements, meta-analyses and leading institutional protocols.

- Relevant Egyptian publications.

- All statements were graded according to strength of clinical practice recommendations, expressed as strong or weak. While this was guided by other guideline recommendations, it was modified to suit the Egyptian environment dominated by a rich bioecological environment, specific demographics and social constraints and limited financial resources.

I.3.2 EPIDEMIOLOGY

I.4 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION (Medical History)

I.4.1 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

I.4.2 The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)

I.5 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION (Assessment of erectile function)

I.5.1 Diaries

I.5.2 Physical examination, digital rectal examination (DRE) and focused neurologic examination.

I.5.3 Urine Analysis

I.5.4 Renal function measurement

I.5.5 Prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

I.5.5.1 Prediction of carcinoma of the prostate (PCa)

I.5.6 Post-void residual urine [PVR]

I.5.7 Uroflowmetry

I.5.8 Imaging

I.5.8.1 Upper urinary tract imaging

Ultrasound allows for assessment of renal masses, hydronephrosis and simultaneous evaluation of the bladder, PVR and prostate size and morphology. It can be used for the evaluation of haematuria, or urolithiasis. Ultrasound is of lower cost, radiation free (22), however it is operator-dependent.

I.5.8.1.1 Imaging of the Prostate

Prostate imaging is mostly done by transabdominal or Transrectal US [TRUS]. Other imaging modalities include computed tomography (CT),

and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Prostate volume predicts symptom progression and the risk of complications. (22)

It's important to assess prostate size and shape prior to treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) and before choosing the surgical treatment modality [open prostatectomy (OP), enucleation techniques, transurethral resection, transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP), or minimally invasive therapies]. Transrectal US is superior to transabdominal route for assessment of volume of prostate (23).

Median lobe enlargement is considered a contraindication for some minimally invasive treatments.

I.5.8.1.2 Urodynamic (UDS)

Pressure flow study (PFS) and filling cystometry are performed to assess male LUTS due to BPO. The role of urodynamic testing in male LUTS due to BPO includes identifying the pathophysiologic events in patients with LUTS during voiding, predicting the outcomes of treatment especially when invasive surgical intervention is considered and making causal diagnosis in patients with inconclusive other tests.

Urodynamic tests also differentiate between bladder outlet obstructions [BOO], detrusor underactivity and detrusor overactivity. (24)

I.5.8.2 Non-invasive tests in diagnosing BOO in men with LUTS

These tests include prostatic configuration/intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP) (25), Bladder/ detrusor wall thickness and ultrasound-estimated bladder weight (26). Other non-invasive urodynamic testing includes penile cuff method (external condom), Prostatic urethral angle and Resistive index (27-29) are not validated for use in the assessment of male LUTS.

Table I:1 Recommendations for diagnosis of male non-neurogenic LUTS

Recommendation

strength rating

1. Take a complete medical history from men with LUTS Strong

2. Use IPSS or its validated Arabic form in the primary assessment of male LUTS, monitoring treatment response and for research purposes Strong

3. Consider assessment of patients’ sexual function before starting any modality of active treatment for BPH [medical, surgical or minimally invasive] Strong

4. Advise the BPH patient to record a bladder diary for at least 48 hours Strong

5. Perform physical examination, DRE and focused neurological examination for male patients with LUTS Strong

6. It is crucial to perform urinalysis for male patients with LUTS. Strong

7. Assess renal functions:

- If there is evidence of Renal impairment (based on history and clinical examination)

- If there is hydronephrosis

- Before surgical treatment for male LUTS.

Strong

8. PSA measurement is important if it helps in the diagnosis or selecting treatment option for LUTS due to BPO. Strong

9. Measure prostate-specific antigen (PSA) if a diagnosis of PCa will change management. The potential benefits and harms of

using serum PSA testing to diagnose PCa in men with LUTS should be discussed with the patient. Strong

10. Measure PVR in the initial assessment of male LUTS and before prescribing medical

treatment for BPH, using transabdominal ultrasound Strong

11. Perform uroflowmetry in the initial assessment of male LUTS. Weak

12. Perform uroflowmetry before starting medical or invasive treatment and for follow-up to assess the treatment outcomes. Strong

13. Perform ultrasound of the upper urinary tract in men with LUTS if there is elevated renal functions Strong

14. Perform prostate imaging when considering 5-ARIs treatment for male LUTS or considering surgical treatment Strong

15. Voiding cystourethrogram (VGUG) is not recommended in the routine diagnostic work-up of men with BPH Strong

16. Retrograde urethrography may additionally be useful for the evaluation of suspected urethral strictures Strong

17. Urethrocystoscopy should be performed in men with LUTS before invasive or minimally invasive treatment if the endoscopic findings may change the treatment option Strong

18. Patients with history of microscopic or gross heamturia, urethral stricture, or bladder cancer who present with LUTS should undergo urethrocystoscopy during diagnostic evaluation Strong

19. Pressure-flow studies (PFS) should be individualized according to certain indications prior to invasive treatment:

- In men who have had previous failed invasive treatment for their LUTS

- In men undergoing invasive treatment for their LUTS and cannot void > 150 mL.

- In men with bothersome voiding LUTS considering invasive treatment and high Qmax > 10 mL/s or high post void residual > 300 mL

- In men with bothersome voiding LUTS considering invasive treatment with aged < 50 years or > 80 years.

- In men with BPH and known or suspected neurological diseases (multiple sclerosis, Parkinsonism, lumbar disc prolapse, diabetes mellitus) considering invasive treatment

Strong

20. Do not offer non-invasive diagnostic tests as an alternative to pressure-flow studies for diagnosing BOO in men Strong

I.6 Conservative treatment (Watchful waiting, WW)

Minority of the men who are not bothered by their LUTS may occasionally progress to AUR and complications, however hand most of them (about 79 %) usually remain stable for many years (30).

Studies comparing WW and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) in men with moderate LUTS showed that the surgical group had improved bladder function (flow rates and PVR volumes), especially in those with high levels of bother. 36% of WW patients crossed over to surgery within five years, leaving 64% doing well in the WW group (31). Increasing symptom bother and PVR volumes are the strongest predictors of clinical failure. Men with mild-to-moderate uncomplicated LUTS who are not too troubled by their symptoms are suitable for WW, which is a type of strategy in which the patient is receiving no treatment but on the other hand he is regularly followed- up by his health care provider (32)

Table I:2 Recommendations for conservative treatment of male non-neurogenic LUTS due to BPH

Recommendation

strength rating

1. Patients should share in decisions about their care and treatment with their healthcare providers. Strong

2. Men who are troubled by their symptoms should be assessed prior to treatment to establish symptom severity and detect complications (most patients are uncomplicated and mild to moderate symptoms) Strong

3. Watchful waiting (active surveillance) should be offered as the preferred option in:

- All patients with mild symptoms of LUTS secondary to BPH (AUA-SI score <8)

- Patients with moderate or severe symptoms (AUA-SI score ≥8) who are NOT bothered by their LUTS

Strong

4. Drug treatment can only be offered when conservative therapy has failed or is not appropriate Strong

5. Lifestyle advice, behavioural and dietary modifications are part of WW. This entails education about the natural history of the disease, reassurance (that BPH is not precancerous) and periodic monitoring (first time after 6 months, then yearly as long as there is no deterioration of symptoms and/or appearance of new complaints. Lifestyle advice includes:

- Restriction of fluid intake at specific times e.g., at night or when going out in public)

- Avoidance/moderation of intake of caffeine or cola, which may have a diuretic and irritant effect, thereby increasing fluid output and enhancing frequency, urgency and nocturia

- Use of double-voiding technique

- Urethral milking to prevent post-micturition dribble

- Reviewing the medications and optimising the time of administration or substituting drugs for others that have fewer urinary side effects

- Treatment of constipation

Strong

I.7 Pharmacological treatment

I.7.1 Alpha Blockers

The prostate and bladder neck have α-adrenergic innervation which is responsible for the “dynamic‟ component of bladder outlet obstruction.

The bladder neck and trigone receptors and also the receptors in the prostate capsule are mainly alpha-1A.

Alpha blockers are thought to work by relaxing smooth muscles thereby reducing this resistance and improving symptoms and flow rate (33)

α1-adrenoceptors in blood vessels, other non-prostatic smooth muscle cells,

and the central nervous system may mediate adverse events. (34)

Alpha-1-blockers can reduce both storage and voiding LUTS. IPSS reduction and Qmax improvement during α1-blocker treatment appears to be maintained over

at least four years (35)

Indirect comparisons and limited direct comparisons between α1-blockers demonstrate that all α1-blockers have similar efficacy in appropriate doses (36,37)

Selective alpha 1-A blockers (Tamsulosin and Silodosin) are as effective as older non-selective alpha blockers (Alfuzosin, doxazosin, terazosin),

however with less likely cardio-vascular events that are common with the non-selective alpha blockers (postural hypotension, dizziness and ECG changes).

Neither prostate size nor age correlate with α1-blocker efficacy in short term (less than one year) follow -up studies, however α1-blockers seems to be more effective in patients with smaller prostates (< 40 mL) in longer-term studies (38). Until recently Alpha 1-blockers seemed to have no effect on AUR prevention in long-term studies,

however, recent evidence suggests that their use may improve resolution of AUR (39).

The first report on intra-operative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS) was in cataract surgery in 2005. Meta-analysis showed that patients using α1-blockers,

whatever the type, has IFIS increased risk. However, the risk for IFIS was much higher for tamsulosin. (40).

Ejaculatory dysfunction (EjD) seems to be reported more common with α1-blockers than with placebo. Tamsulosin and silodosin reported statistically high incidence of EjD than placebo. On the other hand,

both doxazosin and terazosin were associated with less incidence of EjD (41).

I.7.2 5- alpha reductase inhibitors

The androgen that nourishes the prostate gland is dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which results from reduction of testosterone by the enzyme 5α-reductase.

5-alpha reductase has two-types:

- Type 1: predominant expression and activity in the skin and liver (finastride)

- Type 2: predominant expression and activity in the prostate (dutasteride)

The main effect of 5α-reductase inhibitors is inducing apoptosis of prostatic epithelial cells (42), thus reducing the prostate volume by about 18-28% after six months. They also cause a decrease in circulating PSA levels of about 50% after six to twelve months of treatment (43). Contrary to alpha blockers, in the PLESS study, finasteride reduced the relative risk of AUR by 57% and need for surgery by 55% (absolute risk reduction 4% and 7%, respectively) at four years, compared with placebo (44). Furthermore,

finasteride might reduce blood loss during transurethral prostate surgery, probably due to its effects on prostatic vascularisation. (45)

The most relevant adverse effects of 5-ARIs are related to sexual function, and include reduced libido, erectile dysfunction and less frequently,

ejaculation disorders such as retrograde ejaculation, ejaculation failure, or decreased semen volume. They may also cause gynecomastia and breast tenderness.

I.7.3 Muscarinic Receptor Antagonists

Bladder contraction is mediated via the parasympathetic cholinergic nerves. Anticholinergics may also reduce the sensation of urgency during bladder filling and therefore increase the functional bladder capacity. Antimuscarinics (anticholinergics) improve the storage component of male LUTS whether due to BPH or not. Antimuscarinics reduce frequency, urgency, and urgency incontinence episodes (46). They may be used in elderly men and those with significant BOO. There is little evidence of safety in men with high PVRs, however some guidelines prefer cut-off value of 150 ml (1) while others suggest 250 ml (4).

Evidence shows that alpha-blockers combination with antimuscarinics can improve men with both voiding and storage symptoms (47).

Adverse events include dry mouth, dizziness, cognitive affection, dry eyes,

constipation and theoretical risk of urine retention in males with increased PVR. They should not be used in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma.

I.7.4 Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors

The exact mechanism of PDE5Is on LUTS is not completely understood. Many theories have been suggested including reduced smooth muscle tone of the detrusor, prostate and urethra, while others suggest alleged altered reflex pathways in the spinal cord and neurotransmission in the urethra, prostate, or bladder. Increase blood perfusion and oxygenation in the LUT have also been suggested,

together with an anti-inflammatory effect on the prostate and bladder (48,49).

Clinical trials of several selective oral PDE5Is have been conducted in men with LUTS and all of them showed good efficacy in treatment of LUTS due to BPH, however only tadalafil (5 mg once daily) has been licensed for the treatment of male LUTS due to its longer half-life. The noted reduction in LUTS was not correlated to age, pre-treatment testosterone level or prostate volume (50-52). PDE-5 inhibitors are contraindicated in patients who have had a recent myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris or stroke, or those using the non-selective α1-blockers doxazosin and terazosin, nitrates,

potassium channel opener nicorandil. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors improve IPSS, QoL and IIEF score, but not Qmax.

I.7.5 Beta-3 agonists

Beta-3 adrenoceptors are the main beta receptors distributed in smooth muscle cells of the detrusor and when stimulated, detrusor relaxation occurs (54). It has been shown that this category of drugs significantly

improves all OAB symptom score items and also improves the storage sub- score of the IPSS when studying their add-on effect to alpha blockers (55-56).

I.7.6 Phytotherapy or Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM)

Many studies and Cochrane meta-analyses report no statistically significant improvement in IPSS, Q max, PVR, QoL and prostate volume between different phytotherapies compared to placebo (57,58).Many studies and Cochrane meta-analyses report no statistically significant improvement in IPSS

, Q max, PVR, QoL and prostate volume between different phytotherapies compared to placebo (57,58).

I.7.7 Combination therapies

Many authors have tested the efficacy of combination therapy of an α1-blocker, 5-ARI or placebo alone and shown that combination therapy was superior to monotherapy in most of the measured parameters, however the frequency of adverse events was more in combination therapy (59-61).

Combination treatment with α1-blockers and antimuscarinics or beta-3 agonists is effective for improving LUTS-related QoL impairment. These combinations are more effective for reducing urgency, UUI, frequency, nocturia, or IPSS compared with α1-blockers or placebo alone for up to one year (62-64).

A combination of PDE5Is and α-blockers has also been recently studied and showed that the combination is better than α-blockers alone (65). The combination of PDE5Is with 5 alpha reductases have been also studied but to a lesser extent (66).

I.7.8 Desmopressin

As per table 3.

I.7.9 Post micturition dribbling

Post void urethral milking is a technique used to eliminate post micturition dribble (PMD), which is not associated with obstruction but may be caused by the urethra being emptied incompletely by the muscles surrounding it.

This technique involves drawing the tips of the fingers behind the scrotum and pushing up and forward to expel the pooled urine (68).

Table I:3 Recommendations for pharmacological treatment of male LUTS due to BPH

Recommendation

strength rating

1. Offer alpha 1-adrenergic blockers (Alpha Blockers available in Egyptian market: alfuzosin, doxazosin, terazosin, tamsulosin and Silodosin)

as the first line treatment option for patients with bothersome, moderate to severe LUTS secondary to BPH (AUA-SI score ≥8) Strong

2. Offer alpha 1-adrenergic blockers for those who failed conservative treatment as a first line treatment Strong

3. Give the patient a period of 2 weeks to fully appreciate the clinical effect of the prescribed alpha blocker, however significant efficacy over placebo can occur within hours to days. Strong

4. Offer alpha 1- blockers to improve the two components to LUTS (storage and voiding), which appears in significant improvements in IPSS and Q max, which is mostly maintained for about 4 years. Strong

5. Do not offer alpha 1-blockers with the aim of reduction of prostate size Strong

6. Titrate the dose of Doxazosin and Terazosin and monitor blood pressure when offering these alpha blockers for treatment of BPH Strong

7. Warn the patients of ejaculatory disorders when prescribing selective alpha-1A blockers such as Tamsulosin and Silodosin

Strong

8. The choice of the alpha blocker should put into consideration the patient’s comorbidities, side effect profiles, tolerance and economic issues. Weak

9. Offer treatment with any of the two types of 5-ARIs (type 1 and 2) in men with moderate-to-severe LUTS with prostate volume more than (30 - 40 mL) and/or elevated PSA concentration (> 1.4-1.6 ng/mL). Strong

10. Do not offer 5-ARIs for immediate relief of LUTS due to the slow onset of action ranging from 3-6 months. Strong

11. Offer 5-ARIs to decrease the prostate volume on long term use. They can also prevent the risk of AUR and need for surgery. Weak

12. Offer 5-ARIs as treatment alternative for refractory hematuria due to prostatic bleeding, and also preoperatively in BPH cases that present with hematuria Weak

13. Prescribe muscarinic receptor antagonists as a single treatment, however cautiously, in management of male voiding LUTS Weak

14. Offer antimuscarinics only if residual urine volume is estimated to be less than 150 ml Weak

15. Regularly evaluate PVR urine in BPH patients on anitmuscar Strong

16. Advice patient to discontinue medication if worsening voiding LUTS or urinary stream is decreased after initiation of therapy Strong

17. Use long-acting phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors as a single treatment for patients with bothersome, moderate to severe LUTS secondary to BPH (AUA-SI score ≥ 8) whether they suffer from erectile dysfunction or not Strong

18. Do not prescribe PDE-5 inhibitors in patients using nitrates, potassium channel opener nicorandil, or the α1-blockers doxazosin and terazosin, in patients who have unstable angina pectoris, and those who have had a recent myocardial infarction or stroke Strong

19. Combination therapy using alpha blockers and PDE-5 inhibitors seem better than either alone Weak

20. Offer beta-3 agonists alone in men with moderate-to-severe LUTS who present mainly with storage symptoms (frequency, urgency and urgency incontinence) Weak

21. Prescribe beta-3 agonists only if residual urine volume is estimated to be less than 150 ml Weak

22. Monitor PVR in patients on beta-3 agonists regularly Weak

23. Do not offer beta-3 agonists in patients with severe uncontrolled hypertension Strong

24. Do not offer dietary supplement or combination phytotherapeutic agents as standard therapy for the management of LUTS secondary to BPH Strong

25. Offer combination treatment with an α1-blocker and a 5α-reductase inhibitor to men with moderate-to-severe LUTS and an increased risk of disease progression (e.g. prostate volume > 40 mL). Strong

26. Offer patients successfully treated with combination therapy the option of discontinuing the alpha-blocker after 6 months. If symptoms recur, the alpha-blocker should be restarted (conditional recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence). Weak

27. Offer antimuscarinics or beta-3 agonists to alpha blockers in patients with persistent storage LUTS during α1-blocker mono-therapy treatment Strong

28. Use the combination of PDE5Is and α-blockers for those not responding well to the use of either of the drugs as a monotherapy, especially those with erectile dysfunction Strong

29. Offer Low-dose Desmopressin as a therapeutic option in men with LUTS/BPH with nocturnal polyuria if other medical causes have been excluded as a cause of nocturnal polyuria and if patients did not benefit from other treatments (67) Strong

30. Monitor serum sodium 3 days after the first dose. Re-check again after one month. If serum sodium is reduced to below the normal range, stop desmopressin treatment. Strong

I.8 Surgical treatment

I.8.1 Monopolar Transurethral Resection of Prostate (M-TURP)

M-TURP is the standard surgical treatment for BPH since many decades. It has been proven to be efficacious with durable outcomes in terms of decreased I-PSS score, elevated Qmax, improved QoL and decreased PVR urine levels (69).

Intraoperative and short-term postoperative complications include TUR syndrome (0.8-2.5%), blood transfusion (2-4.4%), clot retention (4.9-7.2%) and significant UTI (4-6%). Mid to long term complications include retrograde ejaculation (55-85%), stress urinary incontinence (0.6-1.5%), bladder neck contracture (2-3%) and urethral stricture (3.4-4%). The procedure has overall relatively low incidence of morbidity, which increases with increased prostate size (69-72).

I.8.2 Transurethral Incision of Prostate (TUIP)

Incising bladder neck down to the verumontanum has been used as alternative to conventional TURP with prostate size around 30 g, showing comparable LUTS improvements and increased Qmax (73). An Egyptian RCT comparing TUIP and TURP in prostate size < 30g found no significant differences in terms of I-PSS score, need for blood transfusion and reoperation. TUIP showed favorable results over TURP concerning sexual complications (ED 8% vs. 20%, retrograde ejaculation 30% vs. 70% respectively) (74)

I.8.3 Transurethral Bipolar Resection of Prostate (B-TURP):

With the advent of bipolar trans urethral technology, resection could be carried out in isotonic saline, where the closed circuit of the current is situated locally at the resection site, with no need for returning pole as the grounding pad.

Short term results proved to be comparable to M-TURP in terms of efficacy, with more favorable safety criteria and reduced side effects (blood transfusion, clot retention and TUR syndrome) (73). Long term results showed comparable results in terms of efficacy and complications as well (73-75). This technique could be used safely in patients with large prostates and other comorbidities such as cardiac patients and bleeding tendencies.

I.8.4 Transurethral Bipolar Vaporization of Prostate (BVP):

Although short term results show comparable efficacy with TURP and more favorable safety profile, with lower perioperative morbidity, data still is lacking to identify mid to long term efficacy and complications (75)

I.8.5 Transurethral Bipolar Enucleation of the Prostate (BEP):

It has comparable efficacy and safety profile with HoLEP in substantially large prostates more than 80 g (75-77)

I.8.6 Open Simple prostatectomy:

Open prostatectomy could be performed by either trans vesical (Freyer’s) approach or retro pubic (Millin’s) approach. This is the most invasive surgical treatment option for substantially large prostates more than 80gm. Other less invasive endoscopic procedures such as enucleation procedures as HoLEP & BEP proved to have comparable short to mid-term efficacy with open procedures but with superior safety profiles (76,77).

Table I:4 Recommendations for Surgical Treatment of BPH

Recommendation

strength rating

1.Indications of prostatectomy (whatever the technique) include:

- Recurrent or refractory urinary retention

- Recurrent urinary tract infections due to BPH

- Bladder stones or diverticula due to BPH

- Treatment-resistant recurrent haematuria due to BPH

- Upper urinary tract dilatation due to BPO, with or without renal insufficiency.

- Unsatisfied patients with QoL because of LUTS despite conservative or pharmacological treatments

Strong

2.Both monopolar and bipolar TURP can be used for endoscopic removal of prostates in men with BPH and prostate size 30-80 g. Strong

3.Offer bipolar TURP when prostate volume is larger than 80 g, but still, this depends on surgeon’s expertise and resection speed. Offer bipolar TURP in cardiac patients or patients with bleeding tendencies or patients on anticoagulants Weak

4.Junior staff may use cut-off value of prostate size up to 60 g for M-TURP and B-TURP for prostate size 60-80 g until achieving adequate learning curve

Weak

5.Offer TUIP to treat properly indicated men with BPH when prostate size < 30 g, and no middle lobe enlargement Strong

6.BVP may be used as alternative to TURP in prostate size 30-80 g, whenever available and by trained urologists Weak

7. In absence of endoscopic enucleation possibility, consider simple open prostatectomy for treating large prostates more than 80 g in properly indicated patients Strong

I.8.7 Laser transurethral prostatectomy

I.8.7.1 HoLmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate (HoLEP)

HoLEP is considered the endoscopic equivalent of open prostatectomy (OP). Its outcome is comparable to OP in terms of IPSS and Qmax improvement in large prostates (77). HoLEP has less incidence of blood transfusion, shorter hospital stay and shorter catheterization time compared to both TURP and OP (77,78). HoLEP has been safely used in patients on anticoagulants and anti-platelet therapy (78,96).

I.8.7.2 Green light Laser (Photoselective) Vaporization of Prostate (PVP)

PVP utilizes one of 3 different forms of laser of the same wavelength (532 nm) with different power and different fibers design: 80W KTP, 120W LBO and 180W XPS Lasers.

Mechanism of action: The Potassium-Titanyl-Phosphate (KTP) and the lithium triborate (LBO) lasers work at a wavelength of 532 nm. Laser energy is absorbed by haemoglobin, but not by water. Vaporization leads to immediate removal of prostatic tissue. Three “Greenlight” lasers exist, which differ not only in maximum power output, but more significantly in fibre design and the associated energy tissue interaction of each. The standard Greenlight device is the 180-W XPS laser, but the majority of evidence is published with the former 80-W KTP or 120-W LBO laser systems.

Laser vaporization of the prostate using either 80-W KTP, 120- or 180-W LBO lasers is a good option for the treatment of BPH patients who are indicated for surgical intervention with a prostate size of 30-80 g. PVP can be offered as a modality of BPH treatment for those patients on anticoagulants or anti platelet therapy.

- 1. 80W KTP

It has proven equivalent efficacy to TURP at 12 months’ follow-up in terms of Qmax and I-PSS. KTP PVP showed inferior results to TURP concerning incidence of bladder neck contracture, urethral stricture, residual adenoma and need for reoperation (79-81).

- 2. 120W LBO

Short to mid-term objective and subjective outcomes proved to be comparable to TURP with more favorable perioperative complications rate towards PVP concerning blood transfusion, clot retention, duration of catheterization and hospital stay (82).

- 3. 180W XPS

Goliath study showed non-inferiority of 180W PVP to TURP in both functional and subjective outcomes as well as in complications rate (83).

I.8.7.3 Diode laser treatment of the prostate

Diode lasers with a wavelength of 940, 980, 1318 and 1470 nm (depending on the semiconductor used) are used for either vaporization or enucleation of the prostate. A limited number of low-quality RCTs are present in the literature (84). Worth of notice, this modality is still not available in Egypt.

I.8.7.4 Thulium Laser Enucleation of Prostate (ThuLEP)

Long term results of ThuLEP are similar to TURP in terms of PVR, Qmax, I-PSS and QoL. Postoperative results favored ThuLEP over TURP concerning catheter duration, hospital stay and blood loss (85-86)

+

Egyptian Urological Guidelines, First Edition- 2021 27

I.9 Minimally invasive procedures.

I.9.1 Prostatic Urethral Lift (PUL)

This procedure depends on decompressing the prostatic urethra by lateralizing away the prostatic lobes using a cystoscopically-held device, which implants permanent sutures in the lateral lobes. Although PUL showed lower improvements in Qmax and I-PSS when compared to TURP, The QoL score was the same at 2 years’ follow-up as well as need for retreatment due to bothersome symptoms. PUL was superior to TURP in preserving erectile and ejaculatory functions (87). PUL can be offered as an alternative to TURP in patients not fit for this invasive procedure or those willing to preserve their sexual function with prostates less than 70 g and no middle lobe. Worth of notice, this modality is still not available in Egypt.

I.9.2 Transurethral Microwave Therapy (TUMT)

It uses a specialized catheter to emit electromagnetic waves to prostate for thermos-ablative effect. The available data are considered inconsistent with no evidence of long-term efficacy and high retreatment rates (88). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt.

I.9.3 Transurethral Needle Ablation (TUNA)

It uses an endoscopic catheter through which needles are inserted in the prostate to emit radiofrequency waves to create thermal necrosis. There is no sufficient evidence to support the use of TUNA in the continuum of BPH treatment (89). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt.

I.9.4 Prostatic stent

No sufficient evidence to support its use in treating BPH attributed LUTS. It has high incidence of adverse events as migration, faulty insertion and worsening irritative symptoms (90).

I.9.5 Intraprostatic injection of Botulinum Toxin A

No evidence to support its use in treating BPH attributed LUTS. All data from the literature has proven that it has no role for treatment of BPH.

I.9.6 Water vapour thermal therapy

Water vapor thermal therapy (also referred to as transurethral destruction of prostate tissue by radiofrequency generated water thermotherapy) (Rezum ®) may be offered to patients with LUTS attributed to BPH provided prostate volume "<"80g. It may be offered to eligible patients who desire preservation of erectile and ejaculatory function. Three-year results showed sustained improvements for the IPSS, IPSS-QoL and Qmax (91). Worth of notice, this modality is recently introduced in Egypt

I.9.7 Aquablation

Aquablation surgery uses a robotic handpiece, console and conformal planning unit (CPU). The resection of the prostate is done via a water jet from a transurethrally placed robotic handpiece. Pre treatment transrectal ultrasound is used to map out the specific region of the prostate to be resected with a particular focus on limiting resection in the area of the verumontanum. After completion of the resection, electro-cautery via a standard resctoscope or traction from a 3-way catheter balloon are used to obtain hemostasis.

Aquablation may be offered to patients with LUTS attributed to BPH provided prostate volume 3080g. It has a theoretical advantage in preservation of erectile function or ejaculation as conductive heat (and its potential damage of erectile nerves) is not used to remove prostate tissue (92). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt

I.9.8 Prostatic Artery Embolization (PAE)

PAE is a newer, largely unproven minimally invasive modality for BPH. High level evidence remains sparse, and the overall quality of the studies is low. Results also differed between the trials regarding improvements in Qmax. Two trials reported lower flow rates with PAE compared with TURP (93-95), and one trial reported similar flow rates between groups (94). Mean prostate volumes were significantly higher in the PAE group compared with the TURP group at all follow-up time points (94,97).

Table I:6 Recommendations for Minimally invasive procedures for BPH

Recommendation

strength rating

1.Consider prostatic stent placement as an alternative to indwelling catheters in patients with BPH attributed refractory urinary retention and not fit for invasive procedures Weak

2.Do not offer intraprostatic Botulinum toxin-A injection as a treatment option for patients with male LUTS due to BPH Strong

3.Do not offer PAE for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. PAE is not recommended outside the context of clinical trials. Strong

I.10 Indwelling catheters.

Indwelling catheters (transurethral or suprnapubic) could be offered for surgically unfit patients who have failed medical management and are unable to perform clean intermittent selfcatheterisation. They could be an option for those surgically unfit patients with skin wounds and pressure ulcers that are being contaminated by urine. Indwelling catheters can be better coated with anti- bacterial materials to prevent biofilm formation and secure maximum stay without infection

I.11 Post-prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence (PPI)

Table I:7 Recommendations for Post Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence

Recommendation

strength rating

1.Inform patients undergoing radical prostatectomy of all known factors that could affect urinary continence Strong

2.Inform patients undergoing radical prostatectomy that urinary incontinence generally returns to near baseline by one year postoperatively, but may persist and require treatment Strong

3. Instruct patients to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises (pelvic rehabilitation) before radical prostatectomy and six months postoperatively to hasten recovery of urinary continence Weak

4.Exclude the presence of detrusor overactivity (DO) as a cause of PPI Strong

5.Exclude the presence of anastomotic stricture or contractures leading to overflow incontinence. Perform PVR estimation and office cystourethroscopy to confirm the findings Strong

6.Order pressure flow study (PFS) before proceeding to any invasive treatment modality for PPI to exclude other causes of urinary incontinence; at least six months to one year postoperatively Weak

7.Offer duloxetine ONLY to fasten recovery of urinary continence after prostate surgery. It should not be offered as a therapeutic option for PPI due to sphincteric derangement Weak

8.Offer bulking agents to men with mild PPI ONLY with the intent of temporary relief of their urinary incontinence and after meticulous counselling of these patients Weak

9.Offer male slings to men with mild-to-moderate PPI as a treatment option. Patients should be counselled about the possible adverse events of erosion and the possible need for use of CIC Weak

10.Avoid the use of male slings in PPI in the presence of any of the following: severe incontinence, prior pelvic radiotherapy or urethral stricture surgery Weak

11.Offer artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) to men with moderate-to-severe PPI. Patients should be counselled about the possible side effects of infections and malfunctions. AUS implantation should be offered ONLY in expert centers Weak

12.Counsel patients undergoing AUS implantation that AUS will likely lose effectiveness over time, and reoperations are common Strong

13.Offer patients with persistent or recurrent stress urinary incontinence after male slings AUS implantation Weak

I.12 Conclusion

The understanding of the LUT as a functional unit, and the multifactorial aetiology of associated symptoms, means that LUTS now constitute the main focus, rather than the former emphasis on BPH. It must be emphasised that clinical guidelines present the best evidence available to the experts. However, following guideline recommendations will not necessarily result in the best outcome. Guidelines can never replace clinical expertise when making treatment decisions for individual patients, but rather help to focus decisions - also taking personal values and preferences/individual circumstances of patients into account.

I.13 References

1. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilationsof-all-guidelines/

2. American Urological Association Guideline: management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). 2010. http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-(2010-reviewed-andvalidity-confirmed-2014)

3. National Institute for health and care guidelines: 2019 surveillance of Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management (2010) NICE guideline CG97 , www.NICE.org.uk.

4. Canadian Urological Association guideline on male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (MLUTS/BPH): 2018 update: Can Urol Assoc J 2018; 12(10):303-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.5616

5. Marcus J Drake, Fundamentals of terminology in lower urinary tract function Neurourol Urodyn 2018 Aug; 37(S6): S13-S19. doi: 10.1002/nau.23768.

6. Abdel-Hady El-Gilany1 – Raefa Refaat Alam2– Soad Hassan Abd Elhameed3. Severe Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Prevalence, Associated Factors and Effects on Quality Of Life of Rural Dwelling Elderly. IOSR Journal of Nursing a nd Health Science (IOSR-JNHS) e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 5, Issue 3 Ver. VI (May. - Jun. 2016), PP 21-27]

7. Saurabh Bhargava, A. Erdem Canda and Christopher R. Chapple A rational approach to benign prostatic hyperplasia evaluation: recent advances. Current Opinion in Urology 2004, 14:1–6]

8. [Hammad FT1, Kaya MA. Development and validation of an Arabic version of the International Prostate Symptom Score.BJU Int. 2010 May;105(10):1434-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464410X.2009.08984. x. Epub 2009 Oct 26]

9. Yap TL1, Cromwell DC, Emberton M. A systematic review of the reliability of frequency-volume charts in urological research and its implications for the optimum chart duration. BJU Int. 2007 Jan;99(1):9-16. Epub 2006 Sep 6]

10. David RH Christie, Jane Windsor and Christopher F Sharpley A systematic review of the accuracy of the digital rectal examination as a method of measuring prostate gland volume. Journal of Clinical Urology 2019, Vol. 12(5) 361–370]

11. Gerber, G.S., et al. Serum creatinine measurements in men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1997. 49: 697. ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9145973

12. Hong, S.K., et al. Chronic kidney disease among men with lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 1424. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19874305

13. Mebust, W.K., et al. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol, 1989. 141: 243. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2643719

14. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of prostate volume in men

with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1999. 53: 581. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10096388

15. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate specific antigen is a strong predictor of future prostate growth in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. PROSCAR long-term efficacy and safety study. J Urol, 2000. 163: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10604304

16. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume predict long-term changes in symptoms and flow rate: results of a four-year, randomized trial comparing finasteride versus placebo. PLESS Study Group. Urology, 1999. 54: 662. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10510925

17. Djavan, B., et al. Longitudinal study of men with mild symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction treated with watchful waiting for four years. Urology, 2004. 64: 1144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15596187

18. Jacobsen, S.J., et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men: the Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol, 1999. 162: 1301. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10492184

19. Rule, A.D., et al. Longitudinal changes in post-void residual and voided volume among community dwelling men. J Urol, 2005. 174: 1317. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16145411

20. Idzenga, T., et al. Accuracy of maximum flow rate for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction can be estimated from the ICS nomogram. Neurourol Urodyn, 2008. 27: 97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17600368

21. Reynard, J.M., et al. The ICS-’BPH’ Study: uroflowmetry, lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder outlet obstruction. Br J Urol, 1998. 82: 619.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9839573

22. Grossfeld, G.D., et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical overview and value of diagnostic imaging. Radiol Clin North Am, 2000. 38: 31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10664665

23. Loch, A.C., et al. Technical and anatomical essentials for transrectal ultrasound of the prostate. World J Urol, 2007. 25: 361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17701043

24. Lewis, A.L., et al. Clinical and Patient-reported Outcome Measures in Men Referred for Consideration of Surgery to Treat Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Baseline Results and Diagnostic Findings of the Urodynamics for Prostate Surgery Trial; Randomised Evaluation of Assessment Methods (UPSTREAM). Eur Urol Focus, 2019. 5: 340. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31047905

25. Kojima, M., et al. Correlation of presumed circle area ratio with infravesical obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 1997. 50: 548.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9338730

26. Manieri, C., et al. The diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction in men by ultrasound measurement of bladder wall thickness. J Urol, 1998. 159: 761. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9474143

27. Pel, J.J., et al. Development of a non-invasive strategy to classify bladder outlet obstruction in male patients with LUTS. Neurourol Urodyn, 2002. 21: 117.

28. Shinbo, H., et al. Application of ultrasonography and the resistive index for evaluating bladder outlet obstruction in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Urol Rep, 2011. 12: 255. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21475953

29. Ku, J.H., et al. Correlation between prostatic urethral angle and bladder outlet obstruction index in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology, 2010. 75: 1467. 30. Netto, N.R., Jr., et al. Evaluation of patients with bladder outlet obstruction and mild international prostate symptom score followed up by watchful waiting. Urology, 1999. 53: 314. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9933046

31. Flanigan, R.C., et al. 5-year outcome of surgical resection and watchful waiting for men with moderately symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. J Urol, 1998. 160: 12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9628595

32. Brown, C.T., et al. Defining the components of a self-management programme for men with uncomplicated lower urinary tract symptoms: a consensus approach. Eur Urol, 2004. 46: 254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15245822

33. Chapple CR. Alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonist in the year 2000: Is there anything new? Curr Opin Urol 2001; 11:9-16. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/00042307-200101000-00002

34. Nickel, J.C., et al. A meta-analysis of the vascular-related safety profile and efficacy of alphaadrenergic blockers for symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Clin Pract, 2008. 62: 1547.

35. Tsukamoto T, Masumori N, Rahman M, et al. Change in international prostate symptom score, prostate- specific antigen and prostate volume in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia followed longitudinally. Int J Urol 2007; 14:321-4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14422042.2007.01596.x

36. Djavan, B., et al. State of the art on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 2004. 64: 1081

37. Bozlu M, Ulusoy E, Cayan S, et al. A comparison of four different alpha 1-blockers in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients with and without diabetes. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2004; 38:391-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365590410015678

38. Roehrborn, C.G. Three months’ treatment with the alpha1-blocker alfuzosin does not affect total or transition zone volume of the prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2006. 9: 121.

39. Karavitakis, M., et al. Management of Urinary Retention in Patients with Benign Prostatic Obstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol, 2019. 75: 788. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30773327

40. Chatziralli, I.P., et al. Risk factors for intraoperative floppy iris syndrome: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 2011. 118: 730. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21168223

41. Gacci, M., et al. Impact of medical treatments for male lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia on ejaculatory function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med, 2014. 11: 1554

42. Rittmaster, R.S., et al. Evidence for atrophy and apoptosis in the prostates of men given finasteride. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1996. 81: 814. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8636309

43. Naslund, M.J., et al. A review of the clinical efficacy and safety of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors for the enlarged prostate. Clin Ther, 2007. 29: 17.

44. McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, Andriole G, Lieber M, Holtgrewe HL et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 338(9):557-63. (Guideline Ref ID: MCCONNELL1998)

45. Donohue, J.F., et al. Transurethral prostate resection and bleeding: a randomized, placebo controlled trial of role of finasteride for decreasing operative blood loss. J Urol, 2002. 168: 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12394700

46. Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006, 296(19):2319-28. (Guideline Ref ID: KAPLAN2006)

47. Drake MJ, Chapple C, Sokol R, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of single-tablet combinations of solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in men with storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from the NEPTUNE Study and NEPTUNE II open-label extension. Eur Urol 2015; 67:262-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.013

48. Giuliano, F., et al. The mechanism of action of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 506. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23018163

49. Vignozzi, L., et al. PDE5 inhibitors blunt inflammation in human BPH: a potential mechanism of action for PDE5 inhibitors in LUTS. Prostate, 2013. 73: 1391. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23765639

50. Gacci, M., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors alone or in combination with alpha-blockers for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 994. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22405510

51. Pattanaik, S., et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018. 2018: CD010060. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480763

52. Porst, H., et al. Efficacy and safety of tadalafil 5 mg once daily for lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: subgroup analyses of pooled data from 4 multinational, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies. Urology, 2013. 82: 667. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23876588

53. Vlachopoulos, C., et al. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors and related comorbid conditions and medical therapy reported at baseline on the treatment response to tadalafil 5 mg once-daily in men with lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: an integrated analysis of four randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trials. Int J Clin Pract, 2015. 69: 1496. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26299520

54. Andersson, K.E. On the Site and Mechanism of Action of beta3-Adrenoceptor Agonists in the Bladder. Int Neurourol J, 2017. 21: 6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28361520

55. Khullar, V., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of mirabegron, a beta (3)-adrenoceptor agonist, in patients with overactive bladder: results from a randomised European-Australian phase 3 trial. Eur Urol, 2013. 63: 283

56. Ichihara K, Masumori N, Fukuta F, et al. A randomized controlled study of the efficacy of tamsulosin monotherapy and its combination with mirabegron for overactive bladder induced by benign prostatic obstruction. J Urol 2015; 193:921-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.091

57. Tacklind J, Macdonald R, Rutks I, et al. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12: Cd001423 . https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001423.pub3

58. Wilt T, Ishani A, Mac Donald R, et al. Pygeum africanum for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;1: Cd001044.

59. McConnell, J.D., et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med, 2003. 349: 2387. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14681504

60. Kaplan, S.A., et al. Time Course of Incident Adverse Experiences Associated with Doxazosin, Finasteride and Combination Therapy in Men with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: The MTOPS Trial. J Urol, 2016. 195: 1825.

61. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur Urol, 2010. 57: 123. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19825505

62. Drake MJ, Chapple C, Sokol R, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of single-tablet combinations of solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in men with storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from the NEPTUNE Study and NEPTUNE II open-label extension. Eur Urol 2015; 67:262-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.013

63. Kim, H.J., et al. Efficacy and Safety of Initial Combination Treatment of an Alpha Blocker with an Anticholinergic Medication in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Patients with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Updated Meta-Analysis. PLoS One, 2017. 12: e0169248. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28072862

64. Ichihara K, Masumori N, Fukuta F, et al. A randomized controlled study of the efficacy of tamsulosin monotherapy and its combination with mirabegron for overactive bladder induced by benign prostatic obstruction. J Urol 2015; 193:921-6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.091

65. Gacci, M., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors alone or in combination with alpha-blockers for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 994. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22405510

66. Casabe, A., et al. Efficacy and safety of the coadministration of tadalafil once daily with finasteride for 6 months in men with lower urinary tract symptoms and prostatic enlargement secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol, 2014. 191: 727. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24096118

67. Weiss JP, Herschorn S, Albei CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of low dose desmopressin orally disintegrating tablet in men with nocturia: Results of a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel group study. J Urol 2013; 190:965-72 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.112

68. Paterson J, Pinnock CB, Marshall VR. Pelvic floor exercises as a treatment for post- micturition dribble. British Journal of Urology 1997, 79(6):892-7. (Guideline Ref ID: PATERSON1997)

69. Mayer EK, Kroeze SG, Chopra S, et al. Examining the ‘gold standard’: a comparative critical analysis of three consecutive decades of monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) outcomes. BJU Int 2012;112. 110:1595–601.

70. Ahyai, S.A., et al. Meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic enlargement. Eur Urol, 2010. 58: 384.

71. Lourenco, T., et al. The clinical effectiveness of transurethral incision of the prostate: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. World J Urol, 2010. 28: 23.

72. Abd-El Kader O, Mohy El Den K, El Nashar A et al: Transurethral incision versus transurethral resection of the prostate in small prostatic adenoma: long-term follow-up. Afr Jr Urol 2012;18: 29.

73. Omar MI, Lam TB, Alexander CE, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of bipolar compared with monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). BJU Int 2014; 113:24–35.

74. Mamoulakis, C., et al. Bipolar versus monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Urol, 2009. 56: 798.

75. Geavlete, B., et al. Bipolar vaporization, resection, and enucleation versus open prostatectomy: optimal treatment alternatives in large prostate cases? J Endourol, 2015. 29: 323

76. Habib E, Ayman LM, ElSheemy MS, et al. Holmium Laser Enucleation vs Bipolar Plasmakinetic Enucleation of a Large Volume Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Endourol Published Online:28 Feb 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2019.0707

77. Kuntz, R.M., et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates greater than 100 grams: 5-year follow-up results of a randomised clinical trial. Eur Urol, 2008. 53: 160

78. Yin, L., et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus transurethral resection of the prostate: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Endourol, 2013.

79. Thangasamy, I.A., et al. Photoselective vaporisation of the prostate using 80-W and 120-W laser versus transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review with meta-analysis from 2002 to 2012. Eur Urol, 2012. 62: 315

80. Bouchier-Hayes, D.M., et al. A randomized trial of photoselective vaporization of the prostate using the 80-W potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vs transurethral prostatectomy, with a 1-year follow-up.BJU Int, 2010. 105: 964

81. Guo, S., et al. The 80-W KTP GreenLight laser vaporization of the prostate versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): adjusted analysis of 5-year results of a prospective nonrandomized bi-center study. Lasers Med Sci, 2015. 30: 1147.

82. Zhou, Y., et al. Greenlight high-performance system (HPS) 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a metaanalysis of the published results of randomized controlled trials. Lasers Med Sci, 2016. 31: 485.

83. Thomas, J.A., et al. A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial Comparing GreenLight-XPS Laser Vaporization of the Prostate and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Obstruction: Two-yr Outcomes of the GOLIATH Study. Eur Urol, 2016. 69: 94

84. Bach, T. et al. Laser treatment of benign prostatic obstruction: basics and physical differences. Eur Urol, 2012. 61: 317.

85. Yang, Z., et al. Comparison of thulium laser enucleation and plasmakinetic resection of the prostate in a randomized prospective trial with 5-year follow-up. Lasers Med Sci, 2016. 31: 1797.-

86. Chang, C.H., et al. Vapoenucleation of the prostate using a high-power thulium laser: a one-year follow-up study. BMC Urol, 2015. 15:19

87. Sonksen, J., et al. Prospective, Randomized, Multinational Study of Prostatic Urethral Lift Versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate: 12-month Results from the BPH6 Study. Eur Urol, 2015. 68:643.

88. Mattiasson A, Wagrell L, Schelin S et al: Five-year follow-up of feedback microwave thermotherapy versus TURP for clinical BPH: a prospective randomized multicenter study. Urology 2007; 69:91.

89. Hindley R, Mostafid A, Brierly R et al: The 2-year symptomatic and urodynamic results of a prospective randomized trial of interstitial radiofrequency therapy vs transurethral resection of the prostate. BJU Int 2001; 88: 217.

90. Vanderbrink, B.A., et al. Prostatic stents for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr OpinUrol, 2007. 17: 1.

91. Naspro R, Gomez Sancha F, Manica M et al: From "gold standard" resection to reproducible "future standard" endoscopic enucleation of the prostate: what we know about anatomical enucleation. Minerva Urol Nefrol 2017; 69: 446.

92. Gilling P, Barber N, Bidair M et al: WATER: A double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial of Aquablation vs transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2018; 199:1252.

93. Carnevale FC, Iscaife A, Yoshinaga EM et al: Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) versus original and pErFecTED prostate artery embolization (PAE) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): preliminary results of a single center, prospective, urodynamic‐controlled analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2016; 39: 44.

94. Gao Y, Huang Y, Zhang R et al: Benign prostatic hyperplasia: prostatic arterial embolization versus transurethral resection of the prostate—a prospective, randomized, and controlled trial. Radiology 2014; 270: 920.

95. Abt D, Hechelhammer L, Mullhaupt G et al: Comparison of prostatic artery embolization (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: randomized, open label, non‐inferiority trial. BMJ 2018; 361: k2338.

I.5.8.1.1 Imaging of the Prostate

I.5.8.1.2 Urodynamic (UDS)

I.5.8.2 Non-invasive tests in diagnosing BOO in men with LUTS

Recommendation |

strength rating |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

I.6 Conservative treatment (Watchful waiting, WW)

Recommendation |

strength rating |

|---|---|

|

|

|

I.7 Pharmacological treatment

I.7.1 Alpha Blockers

I.7.2 5- alpha reductase inhibitors

- Type 1: predominant expression and activity in the skin and liver (finastride)

- Type 2: predominant expression and activity in the prostate (dutasteride)

I.7.3 Muscarinic Receptor Antagonists

I.7.4 Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors

I.7.5 Beta-3 agonists

I.7.6 Phytotherapy or Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM)

I.7.7 Combination therapies

I.7.8 Desmopressin

I.7.9 Post micturition dribbling

Recommendation |

strength rating |

|---|---|

I.8 Surgical treatment

I.8.1 Monopolar Transurethral Resection of Prostate (M-TURP)

I.8.2 Transurethral Incision of Prostate (TUIP)

I.8.3 Transurethral Bipolar Resection of Prostate (B-TURP):

I.8.4 Transurethral Bipolar Vaporization of Prostate (BVP):

I.8.5 Transurethral Bipolar Enucleation of the Prostate (BEP):

I.8.6 Open Simple prostatectomy:

Recommendation |

strength rating |

|---|---|

|

|

I.8.7 Laser transurethral prostatectomy

I.8.7.1 HoLmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate (HoLEP)

I.8.7.2 Green light Laser (Photoselective) Vaporization of Prostate (PVP)

- 1. 80W KTP

- 2. 120W LBO

- 3. 180W XPS

I.8.7.3 Diode laser treatment of the prostate

I.8.7.4 Thulium Laser Enucleation of Prostate (ThuLEP)

+

Egyptian Urological Guidelines, First Edition- 2021 27

I.9 Minimally invasive procedures.

I.9.1 Prostatic Urethral Lift (PUL)

This procedure depends on decompressing the prostatic urethra by lateralizing away the prostatic lobes using a cystoscopically-held device, which implants permanent sutures in the lateral lobes. Although PUL showed lower improvements in Qmax and I-PSS when compared to TURP, The QoL score was the same at 2 years’ follow-up as well as need for retreatment due to bothersome symptoms. PUL was superior to TURP in preserving erectile and ejaculatory functions (87). PUL can be offered as an alternative to TURP in patients not fit for this invasive procedure or those willing to preserve their sexual function with prostates less than 70 g and no middle lobe. Worth of notice, this modality is still not available in Egypt.

I.9.2 Transurethral Microwave Therapy (TUMT)

It uses a specialized catheter to emit electromagnetic waves to prostate for thermos-ablative effect. The available data are considered inconsistent with no evidence of long-term efficacy and high retreatment rates (88). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt.

I.9.3 Transurethral Needle Ablation (TUNA)

It uses an endoscopic catheter through which needles are inserted in the prostate to emit radiofrequency waves to create thermal necrosis. There is no sufficient evidence to support the use of TUNA in the continuum of BPH treatment (89). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt.

I.9.4 Prostatic stent

No sufficient evidence to support its use in treating BPH attributed LUTS. It has high incidence of adverse events as migration, faulty insertion and worsening irritative symptoms (90).

I.9.5 Intraprostatic injection of Botulinum Toxin A

No evidence to support its use in treating BPH attributed LUTS. All data from the literature has proven that it has no role for treatment of BPH.

I.9.6 Water vapour thermal therapy

Water vapor thermal therapy (also referred to as transurethral destruction of prostate tissue by radiofrequency generated water thermotherapy) (Rezum ®) may be offered to patients with LUTS attributed to BPH provided prostate volume "<"80g. It may be offered to eligible patients who desire preservation of erectile and ejaculatory function. Three-year results showed sustained improvements for the IPSS, IPSS-QoL and Qmax (91). Worth of notice, this modality is recently introduced in Egypt

I.9.7 Aquablation

Aquablation surgery uses a robotic handpiece, console and conformal planning unit (CPU). The resection of the prostate is done via a water jet from a transurethrally placed robotic handpiece. Pre treatment transrectal ultrasound is used to map out the specific region of the prostate to be resected with a particular focus on limiting resection in the area of the verumontanum. After completion of the resection, electro-cautery via a standard resctoscope or traction from a 3-way catheter balloon are used to obtain hemostasis.

Aquablation may be offered to patients with LUTS attributed to BPH provided prostate volume 3080g. It has a theoretical advantage in preservation of erectile function or ejaculation as conductive heat (and its potential damage of erectile nerves) is not used to remove prostate tissue (92). Worth of notice, this modality is not available in Egypt

I.9.8 Prostatic Artery Embolization (PAE)

PAE is a newer, largely unproven minimally invasive modality for BPH. High level evidence remains sparse, and the overall quality of the studies is low. Results also differed between the trials regarding improvements in Qmax. Two trials reported lower flow rates with PAE compared with TURP (93-95), and one trial reported similar flow rates between groups (94). Mean prostate volumes were significantly higher in the PAE group compared with the TURP group at all follow-up time points (94,97).

Table I:6 Recommendations for Minimally invasive procedures for BPH

Recommendation

strength rating

1.Consider prostatic stent placement as an alternative to indwelling catheters in patients with BPH attributed refractory urinary retention and not fit for invasive procedures Weak

2.Do not offer intraprostatic Botulinum toxin-A injection as a treatment option for patients with male LUTS due to BPH Strong

3.Do not offer PAE for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. PAE is not recommended outside the context of clinical trials. Strong

I.10 Indwelling catheters.

Indwelling catheters (transurethral or suprnapubic) could be offered for surgically unfit patients who have failed medical management and are unable to perform clean intermittent selfcatheterisation. They could be an option for those surgically unfit patients with skin wounds and pressure ulcers that are being contaminated by urine. Indwelling catheters can be better coated with anti- bacterial materials to prevent biofilm formation and secure maximum stay without infection

I.11 Post-prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence (PPI)

Table I:7 Recommendations for Post Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence

Recommendation

strength rating

1.Inform patients undergoing radical prostatectomy of all known factors that could affect urinary continence Strong

2.Inform patients undergoing radical prostatectomy that urinary incontinence generally returns to near baseline by one year postoperatively, but may persist and require treatment Strong

3. Instruct patients to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises (pelvic rehabilitation) before radical prostatectomy and six months postoperatively to hasten recovery of urinary continence Weak

4.Exclude the presence of detrusor overactivity (DO) as a cause of PPI Strong

5.Exclude the presence of anastomotic stricture or contractures leading to overflow incontinence. Perform PVR estimation and office cystourethroscopy to confirm the findings Strong

6.Order pressure flow study (PFS) before proceeding to any invasive treatment modality for PPI to exclude other causes of urinary incontinence; at least six months to one year postoperatively Weak

7.Offer duloxetine ONLY to fasten recovery of urinary continence after prostate surgery. It should not be offered as a therapeutic option for PPI due to sphincteric derangement Weak

8.Offer bulking agents to men with mild PPI ONLY with the intent of temporary relief of their urinary incontinence and after meticulous counselling of these patients Weak

9.Offer male slings to men with mild-to-moderate PPI as a treatment option. Patients should be counselled about the possible adverse events of erosion and the possible need for use of CIC Weak

10.Avoid the use of male slings in PPI in the presence of any of the following: severe incontinence, prior pelvic radiotherapy or urethral stricture surgery Weak

11.Offer artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) to men with moderate-to-severe PPI. Patients should be counselled about the possible side effects of infections and malfunctions. AUS implantation should be offered ONLY in expert centers Weak

12.Counsel patients undergoing AUS implantation that AUS will likely lose effectiveness over time, and reoperations are common Strong

13.Offer patients with persistent or recurrent stress urinary incontinence after male slings AUS implantation Weak

I.12 Conclusion

The understanding of the LUT as a functional unit, and the multifactorial aetiology of associated symptoms, means that LUTS now constitute the main focus, rather than the former emphasis on BPH. It must be emphasised that clinical guidelines present the best evidence available to the experts. However, following guideline recommendations will not necessarily result in the best outcome. Guidelines can never replace clinical expertise when making treatment decisions for individual patients, but rather help to focus decisions - also taking personal values and preferences/individual circumstances of patients into account.

I.13 References

1. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilationsof-all-guidelines/

2. American Urological Association Guideline: management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). 2010. http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-(2010-reviewed-andvalidity-confirmed-2014)

3. National Institute for health and care guidelines: 2019 surveillance of Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management (2010) NICE guideline CG97 , www.NICE.org.uk.

4. Canadian Urological Association guideline on male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (MLUTS/BPH): 2018 update: Can Urol Assoc J 2018; 12(10):303-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.5616

5. Marcus J Drake, Fundamentals of terminology in lower urinary tract function Neurourol Urodyn 2018 Aug; 37(S6): S13-S19. doi: 10.1002/nau.23768.

6. Abdel-Hady El-Gilany1 – Raefa Refaat Alam2– Soad Hassan Abd Elhameed3. Severe Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Prevalence, Associated Factors and Effects on Quality Of Life of Rural Dwelling Elderly. IOSR Journal of Nursing a nd Health Science (IOSR-JNHS) e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 5, Issue 3 Ver. VI (May. - Jun. 2016), PP 21-27]

7. Saurabh Bhargava, A. Erdem Canda and Christopher R. Chapple A rational approach to benign prostatic hyperplasia evaluation: recent advances. Current Opinion in Urology 2004, 14:1–6]

8. [Hammad FT1, Kaya MA. Development and validation of an Arabic version of the International Prostate Symptom Score.BJU Int. 2010 May;105(10):1434-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464410X.2009.08984. x. Epub 2009 Oct 26]

9. Yap TL1, Cromwell DC, Emberton M. A systematic review of the reliability of frequency-volume charts in urological research and its implications for the optimum chart duration. BJU Int. 2007 Jan;99(1):9-16. Epub 2006 Sep 6]

10. David RH Christie, Jane Windsor and Christopher F Sharpley A systematic review of the accuracy of the digital rectal examination as a method of measuring prostate gland volume. Journal of Clinical Urology 2019, Vol. 12(5) 361–370]

11. Gerber, G.S., et al. Serum creatinine measurements in men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1997. 49: 697. ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9145973

12. Hong, S.K., et al. Chronic kidney disease among men with lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int, 2010. 105: 1424. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19874305

13. Mebust, W.K., et al. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol, 1989. 141: 243. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2643719

14. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of prostate volume in men

with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology, 1999. 53: 581. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10096388

15. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate specific antigen is a strong predictor of future prostate growth in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. PROSCAR long-term efficacy and safety study. J Urol, 2000. 163: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10604304

16. Roehrborn, C.G., et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume predict long-term changes in symptoms and flow rate: results of a four-year, randomized trial comparing finasteride versus placebo. PLESS Study Group. Urology, 1999. 54: 662. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10510925

17. Djavan, B., et al. Longitudinal study of men with mild symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction treated with watchful waiting for four years. Urology, 2004. 64: 1144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15596187

18. Jacobsen, S.J., et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among community dwelling men: the Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status. J Urol, 1999. 162: 1301. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10492184

19. Rule, A.D., et al. Longitudinal changes in post-void residual and voided volume among community dwelling men. J Urol, 2005. 174: 1317. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16145411

20. Idzenga, T., et al. Accuracy of maximum flow rate for diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction can be estimated from the ICS nomogram. Neurourol Urodyn, 2008. 27: 97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17600368

21. Reynard, J.M., et al. The ICS-’BPH’ Study: uroflowmetry, lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder outlet obstruction. Br J Urol, 1998. 82: 619.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9839573

22. Grossfeld, G.D., et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical overview and value of diagnostic imaging. Radiol Clin North Am, 2000. 38: 31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10664665

23. Loch, A.C., et al. Technical and anatomical essentials for transrectal ultrasound of the prostate. World J Urol, 2007. 25: 361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17701043